11 sublime paintings of Salome through the ages

12 Dec 2019

12 Dec 2019

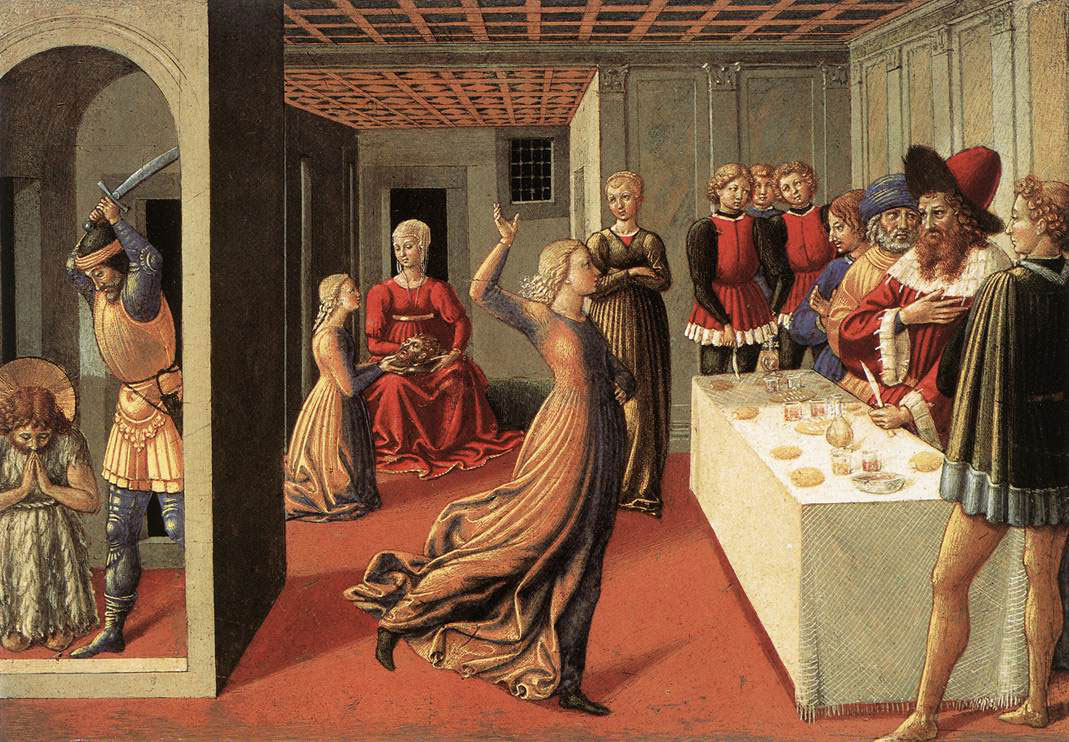

In an altarpiece predella commissioned for a Florentine church, the Italian painter Gozzoli demonstrates his skills as a storyteller, incorporating three episodes from the Gospel of Matthew (14:6-8) in one action-packed frame. In the foreground Salome dances for Herod and his guests at the banquet, while on the left John the Baptist kneels to be beheaded and in the background, Salome presents her mother Herodias with his head.

During the High Renaissance, painters focused their depictions of Salome as young beauty in opposition to a lifeless head. A Milanese painter and follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Solario adorned his Salome with jewels, pearls and textured fabrics – her feminine perfection in stark contrast to the gruesome yellowing head of John the Baptist. She awaits with a demure curiosity for the head to be dropped on a silver plate by the disembodied arm of the executioner.

The German Renaissance painter fostered a fascination with beautiful women carrying severed heads, painting Salomes, Judiths, Lucrecias and other controversial women throughout his career. Dressed in finery of her time, the facial features of this Salome are likely based on a lady of the Saxony court and the landscape in the window evokes Europe. Salome maintains an icy demeanour while Saint John’s eyes almost plead with the viewer, the unusual proportions drawing attention to the heads and gaping wound.

In his 1515 painting, the Venetian artist had portrayed a dreamy, almost bemused Salome with some historians identifying a self-portrait in John the Baptist’s head. In this second iteration, Salome’s sensual gaze is focused on the viewer as she holds the head aloft, her dynamic pose alluding to the earlier seductive dance. The bare skin of Salome and hair of Saint John brushing against her forehead evokes an eroticism that was customary in sixteenth-century depictions.

The story of Salome became an obsession for the Italian master in the final years of his career, painting it three times. With characteristic use of contrasting light and dark, Caravaggio’s 1609 work has a melancholic mood as Salome looks away from the head with a distressed, almost tear-stained expression. Dramatic light cuts across Salome’s chest, the serene head and the muscular arm of the executioner, highlighting the bold red of Salome’s robe.

The only painting in this list by a female artist and one of the first paintings to show Salome looking directly at John the Baptist’s head. Gentileschi drew on her struggles as a woman in seventeenth-century Italy in her art, and here she gives her Salome agency and plays with the gaze. Salome holds out the platter to get a good look at the severed head as the executioner gazes at her with awe-struck ardour.

The French Symbolist painter depicted the subject of Salome more than 150 times in his art. In this hallucinatory watercolour set against a lavish background inspired by the Alhambra, a bejewelled, bare-breasted Salome points in anticipation at the head of John the Baptist levitating in an eerie glow and dripping blood into a large stain on the floor. The Apparition was one of the inspirations for Oscar Wilde’s play.

Known for his Orientalist subjects, the acclaimed Salon painter uses sumptuous colours and his first-hand experiences in the Middle East to emphasise the exoticism of the Salome story, a trend that was fashionable at the end of the nineteenth century. In a columned hall full of Egyptian and Assyrian motifs and artefacts, a scantily clad Salome in a Cleopatra-like headdress begins her dance in front of an expectant audience.

Moving into the twentieth century Salome was increasingly portrayed as a seductive and dangerous woman. An exponent of German Impressionism, Corinth’s depiction of Salome is deliberately provocative and salacious. With garish makeup like a nightclub dancer, Salome is in the midst of the action with her bare breasts over John the Baptist’s head. She uses her fingers to force open John the Baptist’s eyes while she stares at the executioner’s loincloth.

Following the premiere of Strauss’ opera in 1905 which made the ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’ a focal point, Salome became synonymous with the idea of the striptease. In von Stuck’s representation, Salome is a topless dancer in a hula skirt embellished with oriental jewellery flaunting herself against the backdrop of a starry sky. The head on the platter is still present in the background, highlighted by modernist blue halo and held by a dark figure.

Painted during Klimt’s ‘Golden Phase’ featuring geometric patterns and gold leaf, this composite of the Judith/Salome myth demonstrates the influence of modernism and cubism. The elongated figure with her cold gaze and bold makeup is a femme fatale. Her tense and aggressive pose shows her satisfaction at the decapitation as her clenched hands pull John the Baptist’s head out of a bag.