By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

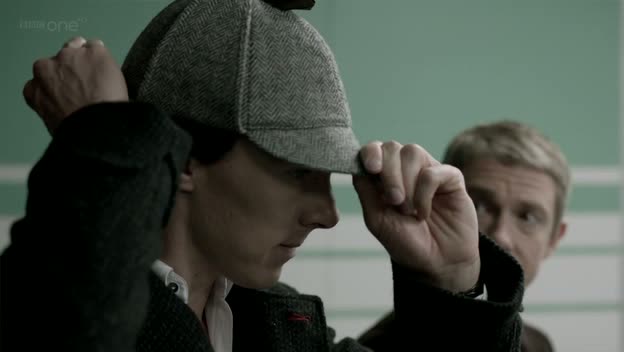

The Case for Benedict Cumberbatch as the Greatest On-Screen Sherlock

Danny Bowes

Who is the greatest on-screen incarnation of Sherlock Holmes? It’s a complicated question — acting can be difficult enough to quantify even without the challenge of taking on the most frequently portrayed fictional character in the history of film and television. Each Holmes has had to compete with and be compared to the ones before him, going back to the anonymous actor who starred in the first Holmes film in 1900, a silent 30-second short from Arthur Marvin.

Of the dozens of actors to take on the role in the over a century since, a few have been truly outstanding, like Basil Rathbone, to whom the highly entertaining cycle of Holmes films in the 1930s and ’40s owe nearly everything. Jeremy Brett’s portrayal of the character on British TV starting in 1984 is widely considered definitive — Brett researched the canonical Holmes meticulously to that end. So I don’t mean it as a slight to either Rathbone or Brett or anyone else who’s played the iconic detective when I say that the greatest performance as Sherlock Holmes is in fact that of Benedict Cumberbatch, star of the BBC’s “Sherlock,” the second series finale of which aired here in the United States last night.

Cumberbatch benefits greatly from the approach taken by “Sherlock” creators Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, Holmes fans who aimed to free the character from what they felt was a paralyzing traditionalism in adaptations. By setting the show in present-day London, they’ve found a way of getting at who Holmes is as a character, giving everyone from the writers to the designers to the actor playing the role the opportunity to focus on who Holmes is, rather than who he has been. While the idea is a fine one, without an adept and delicate execution the whole enterprise would come across as a self-consciously clever literary trick, a game of “how many Holmes references can we fit in one episode,” or, worse, a cynical concession to modern audiences’ disinterest in history and literature.

Cumberbatch benefits greatly from the approach taken by “Sherlock” creators Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, Holmes fans who aimed to free the character from what they felt was a paralyzing traditionalism in adaptations. By setting the show in present-day London, they’ve found a way of getting at who Holmes is as a character, giving everyone from the writers to the designers to the actor playing the role the opportunity to focus on who Holmes is, rather than who he has been. While the idea is a fine one, without an adept and delicate execution the whole enterprise would come across as a self-consciously clever literary trick, a game of “how many Holmes references can we fit in one episode,” or, worse, a cynical concession to modern audiences’ disinterest in history and literature.

Fortunately, Moffat and Gatiss’ “Sherlock” is carried off with remarkable skill, with every creative level of the show combining holistically to create a vivid portrait of Sherlock Holmes as a fully developed person, and not just a bundle of costume choices and famous phrases. Not to downplay the excellence of Cumberbatch’s work, but great performances don’t exist on an island. “Sherlock” is constructed so that the audience sees what Holmes sees, with creative use of camerawork, editing and computer-generated effects. Even establishing shots are selectively blurred to pull focus to one particular area of the shot, as a nod to Holmes’ powers of observation.

As for Cumberbatch’s performance, his physicality is a delight — he alternates between furious activity and catatonic stillness, seeming to be in motion even when still and to exist in a series of meticulously constructed tableaux when in motion. His Holmes is introduced to Martin Freeman’s Watson as a potential flatmate, and proceeds to do an eerily accurate (and signaturely Holmesian) job of sizing Watson up based on a handful of physical details, with the ironic capper of mistaking “Harry” for Watson’s brother, when in fact it’s short for Harriet. Cumberbatch’s Holmes explodes forth with extremely rapid bursts of text when itemizing his observations, his tone an exquisite mix of rigorously academic precision, dry wit, and an almost sensual pleasure in the befuddled awe on the faces of his audiences.

Over the course of the first three-episodes series, we saw many displays of Holmes’ practically supernatural deductive reasoning, as well as his near-complete inability to deal with any other aspect of reality other than his work. Cumberbatch balances Holmes’ investigative genius and his social illiteracy with casual perfection. The fact that he manages to charm and compel in the same beat as he exasperates — as when he crashes Watson’s date with Sarah (Zoe Telford) — and that it feels inevitable that he does so, is a measure of his performance’s quality.

His chemistry with Freeman is also noteworthy; with the latter giving a true supporting performance as well as the odd timely reminder to Holmes that there are other people in the world, people whose value extends beyond being an audience for the detective’s brilliance.

The way Cumberbatch handles these reminders is one of Sherlock’s better running jokes, as he always has some tiny pause or facial twitch to indicate that the moment has registered. And he does learn from these reminders, building to a beautiful blip of a moment in last night’s episode, “The Reichenbach Fall”: after Holmes is arrested, Watson gets himself arrested as well as a sign of solidarity, and for the briefest moment, the corner of Cumberbatch’s mouth twitches. It’s a subtle gesture that revealed that, for all Holmes’ belittling Watson’s intellect and personal life, he genuinely loves his friend — and all in the blink of an eye.

That moment is also a culmination of one of the second series’ new developments in Holmes’ character: fallibility. This idea is introduced with, in keeping with the spirit of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories, the character of Irene Adler (Lara Pulver), one of the few to ever best the sleuth. Here a (controversially) highly sexual manipulator, Irene Adler flusters Holmes and completely nullifies his ability to get an initial read on her by introducing herself to him in the nude.

That moment is also a culmination of one of the second series’ new developments in Holmes’ character: fallibility. This idea is introduced with, in keeping with the spirit of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories, the character of Irene Adler (Lara Pulver), one of the few to ever best the sleuth. Here a (controversially) highly sexual manipulator, Irene Adler flusters Holmes and completely nullifies his ability to get an initial read on her by introducing herself to him in the nude.

Cumberbatch manages to convey the sadly plausible possibility that Holmes may never have had sex before this idea is introduced in dialogue, but doesn’t overplay it. The second-most compelling visual in the scene — besides the obvious — is the way in which Cumberbatch can actually be seen repressing his sexual confusion, in contrast to Watson’s reaction, which Freeman plays as the much more normal “hetero male confronted with staggeringly beautiful nude woman,” by averting his gaze and attempting not to leer.

While the next episode, “The Hounds of Baskerville,” is arguably the series’ weakest, suffering from some suspension-of-disbelief issues and a weak ending, it features a fascinating development in the character of Holmes: his first experience with fear. Cumberbatch plays the scene with the added element of being afraid of being afraid, bringing audiences, having heretofore only known Holmes to be emotionless to the point of autism, into his fear with him. He recovers, but it’s a jarring moment that leads into the climactic final (so far) installment, wherein Holmes confronts his nemesis, the diabolical Moriarty.

“The Reichenbach Fall” features Cumberbatch’s most delicate balancing act yet, his apparently downfall at the hands of Moriarty (the genuinely terrifying Andrew Scott). Someone as self-possessed as Holmes does not unravel easily, and to play that process convincingly requires tremendous skill. Watching Cumberbatch hit not a single false note the entire episode, building toward a very emotional final phone conversation with Watson that both actors play beautifully, is a particular delight, with a final shot that sets up a cliffhanger for the third series so good it almost physically hurts.

“The Reichenbach Fall” features Cumberbatch’s most delicate balancing act yet, his apparently downfall at the hands of Moriarty (the genuinely terrifying Andrew Scott). Someone as self-possessed as Holmes does not unravel easily, and to play that process convincingly requires tremendous skill. Watching Cumberbatch hit not a single false note the entire episode, building toward a very emotional final phone conversation with Watson that both actors play beautifully, is a particular delight, with a final shot that sets up a cliffhanger for the third series so good it almost physically hurts.

“Sherlock” is more than just Benedict Cumberbatch’s show, but it would be nowhere near as compelling without his lead performance. The elements of Sherlock Holmes that tend to get buried underneath his cultural iconography come vividly alive in the actor’s portrayal: his intelligence as a complex quality rather than a set of magic tricks; the alienation that comes with genius; the way that alienation can manifests itself in turning to drugs (in this case, nicotine and a never-named but assumed nod to Holmes’ famous affinity for cocaine); the lack of any but the most transient intimacy; and of course the way in which all these characteristics connect organically to each other. On “Sherlock,” Holmes’ traits never feel as though they’re items ticked off a list compiled from the Conan Doyle stories in Cumberbatch’s hands. He does the near-impossible in allowing us to think of Sherlock Holmes as a real person — and for that alone, Benedict Cumberbatch deserves a salute as the greatest Holmes that ever graced the screen.

[Go HERE for Indiewire’s interview with Cumberbatch.]

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Most Popular

You may also like