- The 500-million-year-old Burgess Shale is home to a newly-identified species.

- Balhuticaris voltae is a gigantic bivalved arthropod with distinctive eyes, segments, and a special shell.

- The Cambrian Period (541 million years ago–485.4 million years ago) saw a huge proliferation of new species.

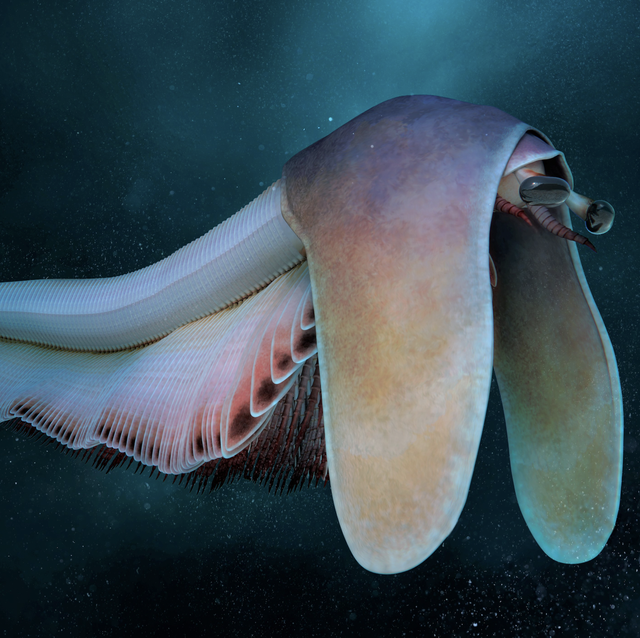

In a surprising twist, a tweet on July 11, announcing an upcoming paper about a new Burgess Shale creature, received nearly 8,000 likes and over 2,000 retweets. The gigantic bivalved arthropod Balhuticaris voltae—distantly similar to today’s crustaceans—has a unique outer shell-body, or carapace, that drapes over its front like the floppy ears of a basset hound.

Burgess Shale animals occupy a huge space in the public imagination, fueled by iconic science writer Stephen Jay Gould’s 1989 book Wonderful Life. The Burgess Shale is a huge deposit of fossils that dates back over 500 million years to the Cambrian Period. Back then, a massive number of animals fell into something like a mudslide and were preserved almost in entirety. That means even their soft tissues, typically lost during the decomposition process when organisms are exposed to the weather, were left intact.

The Cambrian Period that relates to the Burgess Shale is bookended by the Cambrian Explosion just before—an unfathomably large flowering of different species around the planet—and the mass extinction events that followed in intervals after, including the one that infamously killed off the dinosaurs. Between these mass extinctions, almost all the species on Earth were wiped out at different points, bottlenecking our evolution toward the present day.

The Burgess Shale is a special glimpse into an almost unrecognizable time of flora and fauna, with entire animal families that can’t really be linked with anything that exists today. New species are being studied and taxonomized all the time, with well over 200 species discovered to date. The peer-reviewed paper describing the newest one, Balhuticaris voltae, appears in the journal Cell.

Balhuticaris is massive, the authors explain. “This species has an extremely elongated and multisegmented body bearing ca. 110 pairs of homonomous biramous limbs, the highest number among Cambrian arthropods, and, at 245 mm [24.5 centimeters], it represents one of the largest Cambrian arthropods known.”

After seeing his tweet about the new discovery rack up thousands of interactions, Popular Mechanics slid into lead researcher Alejandro Izquierdo-Lopez’s DMs. “[T]he Burgess Shale and its fauna are an iconic fossil site. Most people know only about the animals popularized in the 1980s, but research has intensively continued since then,” Izquierdo-Lopez, an evolutionary biologist, explains. “I am surprised to see the response to Balhuticaris, [but am] glad people are liking this new finding.”

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Popular Mechanics: How did you discover Balhuticaris?

Alejandro Izquierdo-Lopez: Balhuticaris was originally found in the latest Burgess Shale expeditions between 2014 and 2018. I remember seeing a specimen discovered by our collaborator Bob Gaines and was intrigued by it, but could not understand what I was looking at. After observing all ten specimens, by 2020 it was clear we could describe a fully new animal.

Why do you study the Burgess Shale?

I like questions about how evolution works. The idea of the Cambrian Explosion, a time in which most animal groups we know of were young and evolution was experimenting, was very appealing to me. The fossils of the Burgess Shale are some of the best windows into that time period.

What drew you to the bivalved arthropods of Burgess Shale in particular?

My contribution to bivalved arthropods was mostly by chance. The expeditions to the Marble Canyon site of the Burgess Shale had uncovered several new species that needed to be researched, and I just entered at that time. But I have since found out bivalved arthropods are quite an unexplored territory of uniquely shaped animals with a complex ecology, so they are very interesting in themselves.

Balhuticaris has a special carapace that’s almost like a cape. Are there others like it in Burgess Shale that we know of? Is there any analogous creature today?

The carapace of Balhuticaris is quite puzzling. There is nothing like it at the Burgess Shale or in any other arthropod we know of. This is not the first strange carapace we have worked on: Fibulacaris’s ventral spine is also unique.

It’s significant that Balhuticaris is “gigantic,” but why?

Most bivalved arthropods we know of are usually smaller than 10 centimeters. [Balhuticaris is about 24.5 centimeters in size]. There are some exceptions, but they are the majority. Size is an important ecological factor related to what an animal eats and how. The gigantism of Balhuticaris tells us that bivalved arthropods were exploring different ecological positions and can be interesting to understand how prey and predator interactions worked at that time.

What surprised you most during this research?

The most surprising thing about Balhuticaris is the amount of questions it brings to the table. The carapace is strange, but so are its bean-shaped eyes and the high number of segments, a record among Cambrian arthropods. We have had many interesting discussions about how this animal lived, and some will remain unsolved until we discover further anatomical details.

Is there a non-bivalved Burgess Shale creature you admire? What would you study if not the bivalves?

It is quite difficult to choose one! There are animals at the Burgess Shale which we still do not know what they are, like Pollingeria, which looks like an unsegmented worm. These are contestants for groups of animals that either went extinct or we cannot recognize. If not bivalved arthropods, I would study comb jellies. This is a group of jellyfish-like animals that exists today, but also had unique ecologies in the Cambrian.

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and contributing editor at Pop Mech. She's also an enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include nuclear energy, cosmology, math of everyday things, and the philosophy of it all.