Think tank-like festivals can be hit or miss, but I jumped at the chance to attend last week's eighth annual Tom Tom Summit & Festival in Charlottesville, Virginia, and it didn't disappoint. Some 5,000 people showed up for a week of engaging thought leadership on creativity, urban problem solving, and how to build a "creative ecosystem." Here's one of three women I was lucky enough to snag a private audience with.

To say that Melani N. Douglass' work is her life, and vice versa, is not to call her a workaholic. In her day job, Douglass is the director of public programs at Washington D.C.'s National Museum of Women in the Arts. She curates community-building events like the Fresh Talk conversation series, which convenes women working at the intersection of art and social change — art legends like Carrie Mae Weems and Judy Chicago, and poets and authors like Nikki Giovanni and Elizabeth Acevedo.

"Sometimes people do 'community engagement' as a form of marketing — I'm not interested in that at all," Douglass says. Instead, she partners with organizations to bring members of the local community to the talks. The vibe is: "Come with your big questions so we can work them out together," she says.

Connection, vulnerability, and a very personal, human intimacy — what Douglass calls "basic cultural technology" — define her off-the-clock work, too. In 2015, while she was a new mother and still a grad student in curatorial practice at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Douglass declared her own Baltimore home the Family Arts Museum, which she describes as, "a nomadic, non-collecting institution that focuses on family as fine art, home as curated space, and community as gallery." In part, the idea was to offer artists a place to live (at her own expense) so that they could "stop worrying about housing, and focus on making art." The Family Arts Museum (and Douglass herself) now resides in D.C.’s Anacostia neighborhood, and is currently hosting its second resident, Brittany Floyd, whose work focuses on the abolishment of the prison system, and healing and supporting women emerging from incarceration.

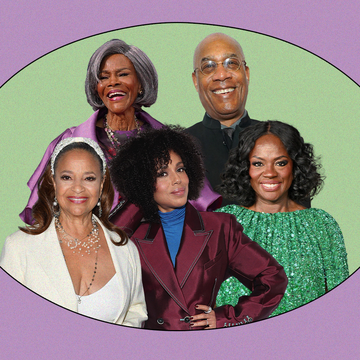

With a riot of curls, gently clinking jewelry, and a wardrobe of exuberantly printed dresses, Douglass in person is the embodiment of the humanity and warmth she preaches. At last week's Tom Tom Summit and Festival in Charlottesville, Virginia, she appeared singularly unguarded: During an on-stage interview, she shared, among other things, her personal Gmail address with the 50-plus attendees. And during the same talk, when her young daughter — unwilling, as any 7-year-old would be, to sit docilely on the front row while her mom was in the spotlight — circled her mother's chair for attention and eventually contended herself by laying her head in Douglass' lap, Douglass intuitively managed her daughter’s needs while holding forth on her own work, never revealing a hint of pique or even distraction. It was an embodiment of the integration of the personal and professional that, for her, is both the simple reality of motherhood and also an act of curation in itself.

Maggie Bullock: What first made you focus on home life as a kind of art?

Melani N. Douglass: My graduate school experience started with Trayvon Martin's murder and then Mike Brown's murder. [In the school program], we weren't talking about what was happening in the world. It was a bubble. Here I had a 15-month-old child I was still nursing. I'd left everything to go back to grad school because I felt strongly about being a mother, about its connection to art, to curatorial practice. And it was traumatic to be in this space every day, feeling these traumas and not talking about it. What I did is really return to home arts. I started crocheting. I amped up my cooking — not really buying food from other places. Organizing a lot at home. The family, the home, became the art that saved me. And then the dryer broke and then I ended up at the laundromat.

MB: That's where you staged an art show, Love on The Line: Stories of a Baltimore Worth Living For

MND: I met Miss Penny [a woman at the laundromat who folded the clothes] and everything about her reminded me of the art of my grandmother: Of cleaning houses and washing clothes of caring for other people's things.

MB: During your talk at Tom Tom, you said working with your grandmother was your first job.

MND: Yes, my first job was as a domestic, cleaning houses with her. If you were a girl, you turned 11 and you went and cleaned houses with her; if you were a boy, you worked in the yard with her partner. I loved it: You're 11-years-old and you have money, you know? My grandmother used her money from cleaning houses to buy land in the neighborhood. I saw this woman who goes to church dressed head-to-toe glamorous [also] in overalls, wielding a machete in the garden — that wide range of womanhood.

MB: You describe that with so much love and dignity, but of course the idea of a woman like your grandmother cleaning other people's houses has a lot of other cultural associations.

MND: That's not my reality. I learned so much from cleaning people's houses. We have this elevated idea of what riches are and what class is. You learn that what someone has in material [wealth], a lot of times they don't have in emotion, in spirit. There are families that say, "My child will never clean a house. They'll never wash a toilet." I get that. But I think being in that space and seeing it, I'm not mesmerized by it. I have seen behind the scenes and it's not always pretty.

MB: Why did you do an art show in a laundromat?

MND: There's a long history of socially engaged art in the laundromat. In 1977, a group of waitresses did a play: The first act was the wash cycle. The second act was the dry. I'm a very ritualistic person. I believe that if you enter a space, you've got to honor the space. Honor what has come before. So [at the art show] you had to bring your clothes. When you came in, you got four quarters, two laundry pods, and two dryer sheet to get you started. Miss Penny was our artist in residence, she did a lesson on how to fold a fitted sheet, which she learned from her mother. And [visitors] had to write love letters to Baltimore. I wanted to hear stories of the Baltimore worth living for, versus one that's about murder.

MB: Folding fitted sheets hits home for me: That's something I learned from my own mother and grandmother.

MND: That's the thing: You could watch a YouTube video, but it's really a skill that has to be passed down to you. That folding of the fitted sheet is definitely one of those.

MB: As a mother, I adore my sons, but I don't always look at cleaning the floor under the baby's high chair as an art. Sometimes I feel conflicted about how much that domestic labor takes me away from work and ideas.

MND: I don't feel that all of the activities we associate with the domestic process are art, only. I feel that the way you go about your mothering is your art. That could mean outsourcing — you say, OK, I have someone that [cleans] this so that I'm able to spend more time doing my work, and the time that I spend with my kids is quality. The same way you value art, that you put money on art — your art as a mother should be just as valued. And it should be just as respected and discussed and analyzed and reviewed and treated as a laboratory to go back and say, "How do I want to do this better? What does better look like for me?" Also it's the art that everybody has access to. Not everyone's going to a museum, but whether your relationship is good or not, you have a family and a community that you engage with. It's that thing that connects us all.

MB: So when you're having a motherhood moment that does not feel like art, what do you tell yourself?

MND: I have what I call a "rocking chair theory." My grandfather lived to be 104. When I'm 104 years old, there are certain things that are just not going to matter.

MB: You've talked about a support "ecosystem" that you're creating as a mother — what do you mean by that?

MND: OK, so, there's something that has created a moon that has this amazing cycle that impacts the water. A sun that has amazing impact on plants, and all this connectivity. I have a hard time believing that whatever created all of that would create me and then expect me to live without some sort of support — a network, an infrastructure, an ecosystem that should allow me to thrive. I don't believe that. On top of that, because I'm a woman, even before I have a child, I'm supposed to have a lesser access to this ecosystem. Crazy. And then if I have a child, I have even less access to this ecosystem. Even though having a child is what makes the ecosystem actually thrive? It makes no sense.

MB: You've fully integrated your child into your career. Most women spend a lot of bandwidth trying to avoid that, or at least to maintain them as two separate spheres.

MND: Yes and I don't think that's healthy. And [we're seeing it shift] as more women are controlling spaces. When I went to grad school, I had say, "Listen, I'm coming but I'm still nursing." So [at school] I had a space to nurse. My daughter had her own shelf, a little tricycle, a box of blocks, her blankets. People knew her. Grad school poverty is real: She wasn't there because I was trying to make some artistic statement. My bank account did not allow for me to have a babysitter for her. So it was like, guess what, here we are.

MB: Did having a child there change the atmosphere of the program?

MND: I think it caused people to see things in ways that might not have. Children do that. Children remind people to be fascinated. And in curatorial process, one of the main things is you cannot lose your fascination. You can't lose your newness to life.

MB: What's in store for the Family Arts Museum?

MND: We're now doing some things to be able to shift it around — we're putting a garden together, we want to do classes on different family arts, like how to make a DIY household cleaner. And also my daughter wants to teach her own yoga classes. We're redoing the wood floor to set up her yoga studio. But everything moves a bit slowly because it's just me: I fund all of it, I do all of it. I need to make it sustainable so it's not contingent on my resources: look for grants, establish an advisory board. I don't necessarily need it to be big — sustainability, impact, and efficiency are my things.

MB: Do you love your work?

MND: I do. I love it because I have one foot in the institution world, the "art museum" world, and I have one foot in the community and engagement world. And I love how I'm able to pick up the phone and invite people out, like, "Who can I have a conversation with just because the work I do is so cool?"

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY