Sherlock Holmes, Unlikely Style Icon

The detective's iconic tweeds, robes, and deerstalker hat came from the imaginations of illustrators and filmmakers far more than from Arthur Conan Doyle himself.

The Museum of London recently debuted Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived and Will Never Die, a major exhibition devoted the fictional detective and the real city he inhabited. The items on display include a rare manuscript of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in Rue Morgue—a key influence on Holmes’s creator, Arthur Conan Doyle—and a portrait of Conan Doyle never before seen in public. But alongside these one-of-a-kind historical treasures, visitors will find two curiously modern artifacts: the coat and dressing gown worn by Benedict Cumberbatch in Sherlock, the BBC’s 21st-century reboot of the Holmes stories.

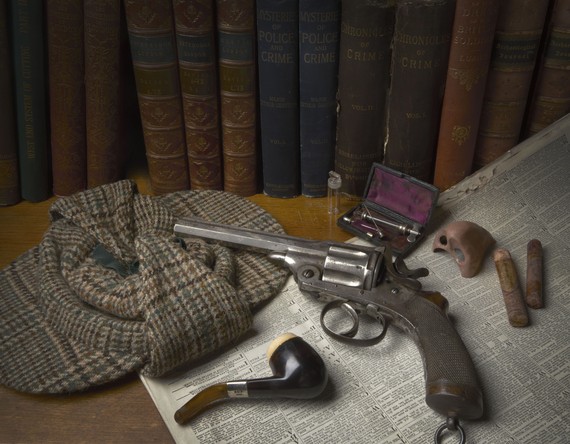

While these costumes are obvious bait for fanboys (and fangirls) who might not be clued into the Victorian literary sensation behind the modern-day television sensation, they also serve as a reminder that Holmes’s fashion choices, from page to screen, have always launched real-world trends. In Conan Doyle’s lifetime, Holmes’s name and likeness were used to advertise pipes and shirts as well as tea, toffee, and mouthwash. More recently, Esquire, FHM, and GQ have advised readers on how to get the Sherlock look. The exhibition provides a retrospective of Sherlockian style, investigating how it has evolved while retaining its instantly recognizable Victorian fashion DNA. The museum even commissioned a Scottish textile mill to create a signature tweed in Holmes’s honor, and a concurrent show features fashion photographer Kasia Wozniak’s prints made using a 1890 field camera.

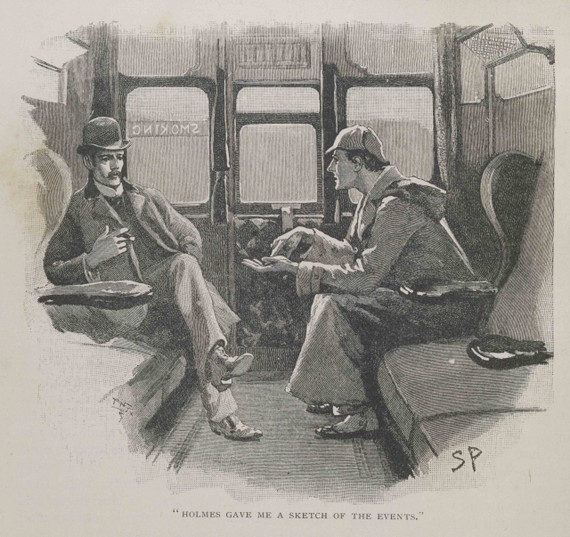

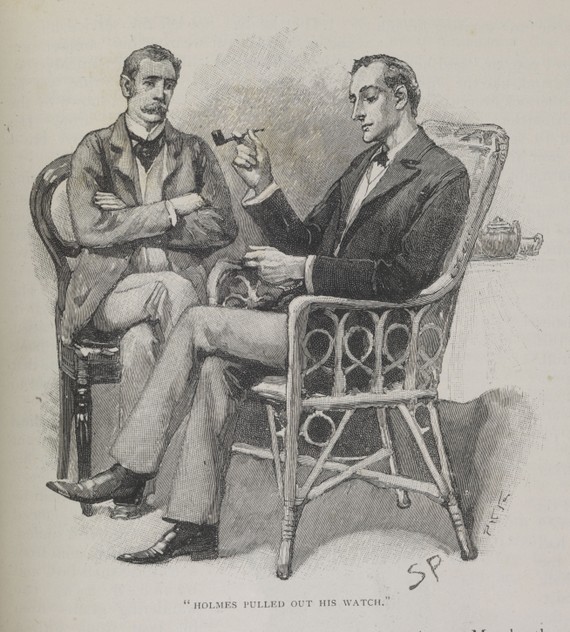

This lasting fashion legacy is all the more extraordinary considering how stingy Conan Doyle was with descriptions of dress. Our image of Holmes comes almost entirely from his illustrator, Sidney Paget, whose elegant, angular prototype influenced every incarnation thereafter. Though he didn’t always share them with readers, however, Conan Doyle clearly had firm ideas about Holmes’s appearance; he once protested that a poster for the 1899 play Sherlock Holmes made the detective look “about five feet high” and “badly dressed.” And Timothy Long, the Museum of London’s fashion curator, points out that Conan Doyle used a “lost language” of fashion. “The modern audience reading these stories often overlooks clues that were very obvious to contemporary readers,” he says. “Putting Watson in a morning coat or a frock coat indicated the time of day, for example.”

Long describes Holmes’s wardrobe as that of “a modern English gentleman. The greatcoat and the deerstalker were key components of any gentleman’s wardrobe in England at that time period.” Thanks to the popularity of the Holmes stories, plays, and films, they remain so in the popular imagination today. Holmes’s clothes in their various iterations are both timeless and very much of their times. The three most indelible Sherlocks—Paget’s original illustrations, Basil Rathbone in the 1930s, and Cumberbatch—all wear contemporary dress, yet they are all unmistakably the same character.

Take that coat, for example. In the stories, Holmes was “enveloped” in an Ulster, a long, single-breasted coat with a small collar and an attached a hip-length cape. Conan Doyle also mentioned an “overcoat” (possibly the same one) and a “long grey travelling-cloak.” These have morphed over time into one stately, billowing garment, lending the character the mystery and panache of a superhero. (The poster for the 1965 film A Study in Terror called Holmes “the original caped crusader.”) Rathbone’s iconic tartan coat was tailored for the big screen, with a more mobile, elbow-length cape and a wide, face-framing collar. Cumberbatch’s coat—an off-the-rack number by British label Belstaff—was inspired not by the Victorian ulster but the 18th-century greatcoat, with its high, stiffened collar and wide lapels. Instead of a cape, its double-breasted front and pleated, belted back provide volume and movement.

With his Ulster, the literary Holmes wore a cravat. Rathbone’s colorful silk scarves look almost feminine today, but they harmonized with 1930s fashions (think Fred Astaire). In Guy Ritchie’s steampunk-inspired Sherlock Holmes movies, Robert Downey Jr.’s flashy ascots are the only recognizably Holmesian aspect of his costumes, even if they seem more appropriate to circa 2008 Brooklyn than Victorian London. Cumberbatch’s blue-gray scarf functions as an extension of his coat (and eyes).

It was Paget who introduced the deerstalker, mentioned nowhere in Conan Doyle’s writings. (Holmes never uttered “Elementary, my dear Watson!” either.) As its name implies, it was a hunting garment, suitable for outdoor pursuits. Paget’s Holmes wore it in the country, never in London. However, Rathbone and subsequent Holmeses wore it everywhere, including indoors. As a trope, the deerstalker improved upon the generic “ear-flapped travelling-cap” Conan Doyle gave his hero. “Holmes never hunted,” exhibition curator Alex Werner reminds us. “But Conan Doyle used the metaphor of hunting to express Holmes’s pursuit of the truth.” Though the deerstalker is no longer a staple of the English gentleman’s wardrobe, it makes an ironic appearance in Sherlock; Cumberbatch impulsively dons one to hide his face from the paparazzi, only to have it become his trademark. (His humiliating nom de tabloid is “Hat Detective.”) Downey, however, wore a fedora, in keeping with his Brooklyn hipster interpretation.

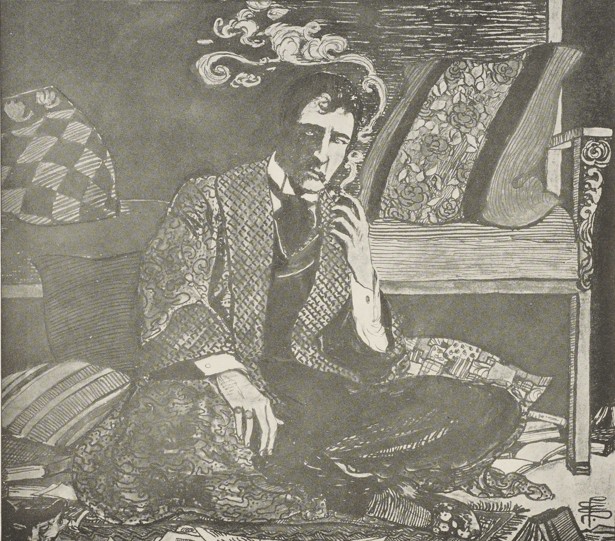

His gentlemanly dress often hid what Conan Doyle called Holmes’s “Bohemian soul.” The melancholy, violin-playing, cocaine-injecting insomniac was betrayed by his off-duty clothes, specifically his collection of dressing gowns, which ranged from “mouse-colored” to a dandyish purple. The camel version on display at the Museum of London is the most subdued of several Cumberbatch wears in the BBC series.

Holmes was well aware of the power of clothing to reveal as well as transform. Anthropometry—a legitimate scientific discipline in the Victorian era—held that physical characteristics corresponded to character traits; Holmes’s high forehead indicated the mighty brain behind it. Clothing, by extension, could do the same—a perfectly reasonable assumption at a time when read-to-wear was in its infancy and those who could afford to still had their clothes custom-made. “Dress is a main character in the stories when it comes to providing clues for Holmes,” Long says. No scuffed shoe or scratched pocketwatch escaped his notice; the smallest sartorial detail could be the key to solving a case. He once deduced an entire psychological history from the “very ordinary black hat” that led him to the famous blue carbuncle.

Holmes’s methods—baffling to Watson—are well known to modern-day costume curators and conservators. “We are quite Sherlockian in our approach,” Long says. “We regularly look at wear marks, labels, and types of materials.” Inspired by the Holmes stories, Long and “an army of volunteers” scoured the museum’s archives for historical garments with tell-tale clues to the wearer’s identity. A pair of men’s evening shoes on display has circular wear marks on the soles, suggestive of dancing; a woman’s blouse with ink-stained sleeves recalls the one that helped Holmes identify his client as a typist in A Case of Identity.

A master of disguise, Holmes had an arsenal of unlikely alter egos, from an old lady to a “simple-minded Nonconformist clergyman.” Long notes that although Holmes’s borrowed makeup and wardrobe techniques from the Victorian stage, his disguises were not particularly theatrical or exotic, but “the disguises of the everyday.” In Sherlock, Cumberbatch has convincingly posed as a French waiter, a Guardsman, a hoodie-clad heroin addict, and a Pakistani terrorist.

But Cumberbatch’s greatest disappearing act is his effortless embodiment of Conan Doyle’s archetypal character: the angular silhouette, the hawk-like profile, the cape-like coat. A distinct lack of physical resemblance may be why the other modern-day TV Holmes, Elementary’s Jonny Lee Miller, has struggled to connect with viewers. Miller (like Downey) is more of a Watson than a Sherlock—compact and muscular rather than tall and lanky. It follows, then, that his clothes also break the mold. A floppy coat would not just envelop but swamp him; instead, a double-breasted pea coat provides warmth in the New York winters, while a red tartan scarf provides what little sartorial panache he possesses. But his endless supply of rumpled vests and ill-fitting blazers convey his Englishness—especially next to Lucy Liu’s quintessentially chic New Yorker of a Watson—while his habit of buttoning his shirts up to the chin telegraphs the character’s OCD tendencies. In this case, however, there’s no mystery why it’s Liu’s Watson wardrobe that has inspired style bloggers.